This article is based on my research paper as part of my MA – Graphic Design Communication. I believe design is learnt by opening our eyes and ears. Wherever we are, design is always present. Whilst there are books, museums, exhibitions, conferences and lectures, my favourite tutor for design is my surroundings. My practice is the accumulated sum of my experiences, travels and the people I’ve met along the way, all of which have been an inspiration.

Is the Japanese duality of uchi and soto challenging the design dictum of “form follows function”? A personal exploration of Japanese packaging and traditional Japanese architecture.

Beauty may lie in the eye of the beholder, but in Japanese architecture what is seen is frequently not there, and far more is present than is actually seen.

Coaldrake, W. Architecture: the AIA Journal, vol 77, 1988

Awakening

My first encounter with Japan was ironically in Annecy, my hometown and capital of the mountainous region of Haute-Savoie in France. It was a present from Noriko, a Japanese exchange student, on my fifteenth birthday that was intricately wrapped in paper embossed with oriental motifs. It was a work of art which I ungracefully tore apart without thought for the wrapping only to be confronted by a decorative paper box which I hastily opened by undoing the ornamental red ribbon to reveal, on a bed of satin lining, a carefully folded handkerchief; the same article that my grand-mere carries tucked in the sleeve of her jumper to blow her nose! I could do little to disguise my disappointment that was amplified by the collective roar of laughter of my friends huddled around me, in anticipation of a CD player or some other object of teen lust. ‘It’s the thought that counts’ was the charitable consolation I offered to an embarrassed Noriko for the failure of the present to match the expectation of its wrapping.

A few years later, I visited Japan on my own and slept in a ryokan (traditional guesthouse) in a room whose moveable doors and walls were literally paper-thin, on the floor made of straw. Earlier in the day, it held a table that we dined on while gazing out at the garden, before moving it aside and unrolling my futon mattresses. A sleepless night ensued from the snoring and shuffling of my neighbours in the adjacent room, the continuous trickling of water from the pond outside, to the birds chirping and morning light bathing the room at the crack of dawn.

Those first encounters with such unique manifestations of Japanese culture evoked my curiosity of Japan. As a fine arts graduate with an interest in languages, it led me to work there only to be further enchanted by its contrasting culture and forms. It is also the driving force behind this paper in an attempt to demystify the phenomenon of Japanese forms.

At the highest level, this paper is about intercultural communication that can be achieved through design and the possibilities for misinterpretation of familiar objects in an unfamiliar cultural context. Based on the Japanese social concepts of uchi (inside) and soto (outside) which denotes a deeper meaning of ‘self’ and ‘society’ whereby the latter is always paramount, it analyses its effect on Japanese forms against modern design theory. This is explored in Japanese packaging and architecture both of which are widely held to be unique and the parallel between these practices in the use of layers as a form of cultural communication to wrap objects, space and society.

1. Uchi and soto

When I lived in Japan, I soon realised that Japanese society is characterised by a plethora of dualities such as modern and tradition, conservative and hospitable, rigid and adaptable, brave and timid (Benedict, 1989). The most important however are the concepts of uchi and soto.

Honne and Tatemae

Uchi and soto literally means ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ but it has far more dimensions than its literal meaning. It denotes, private and public, close and distant relationships, but most importantly ‘self’’ and ‘society’ whereby the polite outer appearance or façade (tatemae) is paramount and is always on display in public. True feelings, desires and opinions (honne) are suppressed out of politeness or to avoid imposing or burdening others and only ever revealed in private to intimate or close relationships. Unlike many societies which value individualism, it goes against the grain of Japan collectivist society where the needs of the group are seen as more important than the needs of individuals. Tatemae is the societal standard which creates a stable comfortable atmosphere and maintains harmony in society.

An example of the concept is annual holidays which I took regularly in Japan to explore the country unlike my Japanese colleagues. One colleague who I became close with later confided in me that as much as she would love to (honne), Japanese workers do not take holidays as it would be irresponsible and selfish and they would feel guilty about increasing the workload of their colleagues (tatemae). Needless to say I curbed the number of holidays I took after.

Uchi and soto and its intertwined connotations are the foundations of the social framework around which every aspect of Japanese life is arranged. Bachnik accurately describes it as ‘a drop of water in a pool, move in ever widening circles to encompass a broad series of issues both inside and outside Japan’ (1994, p.3).

Unsurprisingly the presence of these social constructs is reflected in Japanese designs in the use of layers to create barriers or distance between inside and outside. Indeed, Japan can be said to have wrapped itself in layers during the Edo period (1603 -1868) when it was closed off entirely from the outside world and pursued isolationist foreign policies. It is, therefore, no coincidence that the Japanese character for country 国 kuni, consists of the character for 王 king enclosed by a box 囗; an apt metaphor of itself as a closed country. For this reason, Westerner’s find Japan culture so unique and mysterious as we only see the outer façade and never inside the box.

Soto: gaikokujin

This is visually represented in a short animation I created as an experiment based on the character for foreigner 外国人 gaikokujin, composed of 外 soto (outside) 国 kuni (country) which together means 外国 gaikoku (foreign country) and 人 jin (person) literally meaning ‘outside country person’ (frequently used in its short-form of gaijin or outside person). It depicts 外soto (outside) attempting to get inside 国 kuni (country) by penetrating the outer layer (tatemae). As a Western designer, the animation provides an important clue on why Japanese designs while unique, appear to us to challenge accepted design principles.

2. Challenging design theory?

Louis Sullivan’s ‘form follows function’ is a constant refrain in design theory. While its various interpretations are still a constant source of debate, for the purpose of this paper, it is the general principle that the shape of a building or object should be primarily based upon its intended function or purpose. On the surface, the practice of layering enshrined in the design of Japanese packaging and architecture appears to contradict this principle.

The First Bite Is With The Eye

Meticulous care is paid to packaging everything from mundane groceries such as the humble apple to everyday items such as chopsticks. Items are usually wrapped in cellophane and boxed that is in turn wrapped and placed in a bag on purchase. It is not uncommon for simple items such as fruit to be encased in many as four to six layers of plastic and paper. This layering and attention to detail of packages make even the most mundane objects a visual pleasure. Hideyuki Oka in How to Wrap Five More Eggs, notes that Japanese packaging has become an art form and has ‘transcended its simple role as something in which to wrap certain items and became an end in itself’ (1975).

As a Western consumer, these transient works of art give first impressions and influences our perception of its content. It often also creates high expectations that the content invariably does not match. From a design perspective, these forms with its emphasis on aesthetics goes way beyond its function of preserving, protecting and transporting its contents. In simplistic terms, the logical conclusion that follows is that Japanese packaging challenged accepted design theory.

Outside Inside

Japanese houses also do not conform to the conventional function of a building as a static permanent structure to separate indoor and outdoor. In fact, it seems to be designed to have the exact opposite effect of opening inside to the outside and bringing the outside inside. The separation between inside and outside of a Japanese house is not absolute as entire walls can be removed. Wooden inner shoji (sliding walls covered with translucent paper) create temporal spaces while outer shojis slide back to extend the interior to the veranda and garden and create almost a pavilion. Temporal layers provide a seamless flow between inside and outside, and the boundaries between the two are blurred further by the use of natural materials such as bamboo, wood, paper and straw within the interior for sitting, walking, sleeping and separating.

As a Westerner, it is often difficult to define what is indoors and outdoors of a Japanese house. A veranda and outer rooms (with walls slid back) with tatami mats are outdoors but it is covered by the roof so can also be seen as indoors or ‘open air inside’ or ‘roofed outdoors’.

On the surface, designs in both these practices appear to challenge conventional design principles. But following the clue provided by the gaikokujin animation, perhaps our view is simply that of an ‘‘outside person’’ looking in without having penetrated the cultural façade that encloses Japanese society.

3. Packaging: reading between the layers

A Western perception of the function of objects tends to be defined by practical utility. We regard packaging as a means to protect, transport and perhaps obscure the object inside. Because the experience of opening a package is so integrated into our everyday life, the focus on interest is the object inside and we rarely reflect on its outer layer. Whereas in Japanese society, there might be other cultural functions of packaging that are unknown to an outsider. Yokoyama on packaging remarks:

Japanese believe that the feelings of respect or gratitude of either the presenter or the seller of a package are revealed in the way in which he has wrapped it. Everyone is so sensitive to the way things that they receive are wrapped that if something is wrapped carelessly, they feel that the giver’s intention are not quite what they should be.

Yokoyama, T. Package design in Japan, 1989

Polite packaging

Given the importance of the separation between inside and outside relationships in a society that places high value in the suppression of direct display of emotion, Yokoyama’s comment suggests that packaging functions as a form of non-verbal communication. Ekiguchi asserts ‘In Japan it is said that giving a gift is like wrapping one’s ‘heart’ (1986, p.7). People perhaps use packaging as a form of interaction to communicate politeness, thoughtfulness, respect, humility and considerateness through its specific design features. The number of layers of wrapping is indicative of the formality of the occasion or the distance of relationships. For example, Oka (1975 p.18) suggests that a single layer is used to denote an event such as a funeral as it should only happen once and does not bear repeating. Whereas packaging given to those who are less familiar are often wrapped in more layers. This is premised on the notion that unwrapping each layer plays with the recipient’s imagination of the object’s appearance and its worth. The opening of the package itself is calculatedly designed to increase the longing for the object and maximise the joy of anticipation.

Presentation is everything

I can personally attest to this heightened anticipation in the design of lunchtime bento boxes sold at Japanese train stations. After untying the string which binds the box, opening the lid and removing the bento tray from the box, then lifting the plastic covering to reveal the perfectly arranged contents of the top tray and then separating the top tray from the bottom tray and removing the plastic covering from the bottom tray, one is so caught up in the moment that the feast laid out seemed secondary. This perhaps is another function of packaging in Japan; to derive pleasure from the receipt of a nicely wrapped gift and not the gift itself. If the means of presentation is elegant enough, then the nature of the content may be insignificant.

So it would seem that the practice of layering in packaging functions to refine its content. Rather than an obstacle to overcome, it adds layers of unspoken meaning to the content that is not communicated in its unwrapped form. In focusing just on the content which we are accustomed in the West, ignores the cultural functions built into its design. In attempting to hurriedly penetrate the labyrinth of layers of Noriko’s present to reach its content, I certainly missed the subtle communication of affection, respect and friendship in the layers of wrapping which I so quickly undid and disposed. No wonder it is common practice in Japan to place a gift aside until guests have left, as its immediate opening displays too much interest in the content of the offering rather than in the sentiment it expresses.

The important point from this reflection is that in any culture, a gift of inappropriate value may sour relations. However, in certain cultures, the overall packaging of content has its own function that demonstrates a greater significance to recipients with proportional consequences for inappropriate presentation. In such cultures, form is a function and its own raison d’etre.

4. Spacial wrapping

‘For many Westerners, a house is a thing, an object. But to the Japanese it is a context, or rather a shifting set of smaller contexts within a larger one… not a box with openings, as in the West, but a space-moulding system’ (1988, 14).

Greenbie, H. Space and spirit in modern Japan. 1988

This view of architecture as a space-moulding system provides a potentially interesting parallel with packaging. ‘Can we call buildings and cars packages because they contain people and things?’ (JPDA, 1976).

I first explored this idea in Christo’s works, especially the wrapping of the Museum of Chicago in tarpaulin which changed the museum as a package of art and made it the art itself (1969).

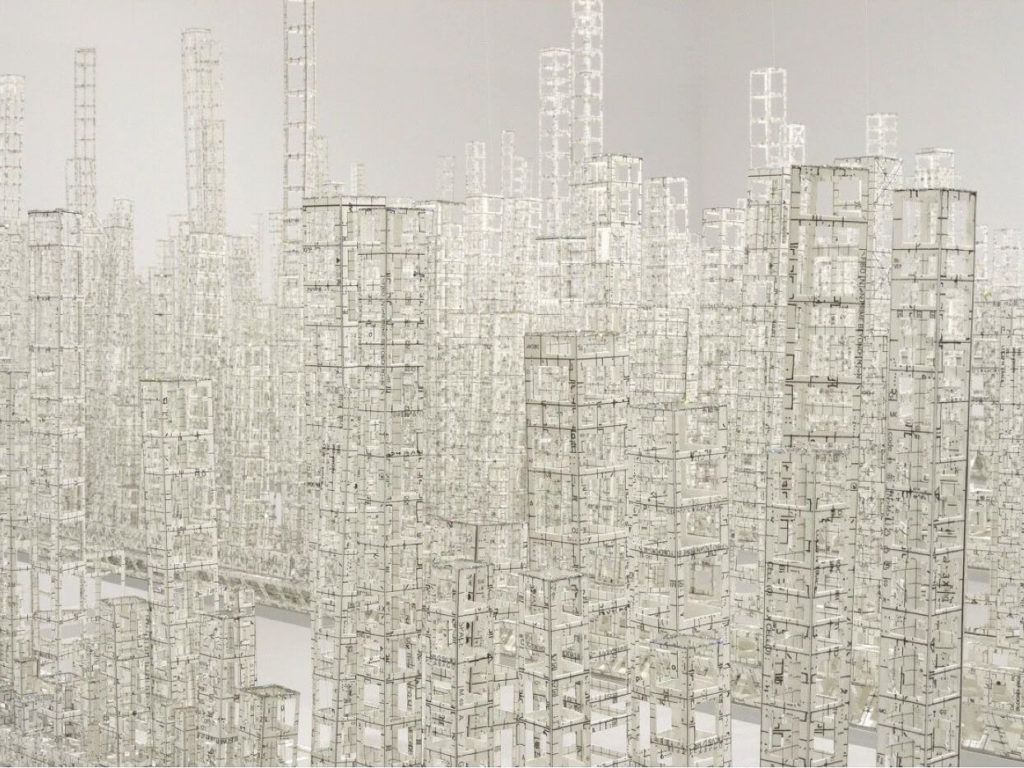

Katsumi Hayakawa’s suspended metropolis Floating City (2011) which depicts utopian urban density, to me portrayed a city represented in its basic form, as a collection of box-shaped paper foundations.

Katsumi Hayakawa investigates the city and the spread of man-made buildings with his hand-made sculptures.

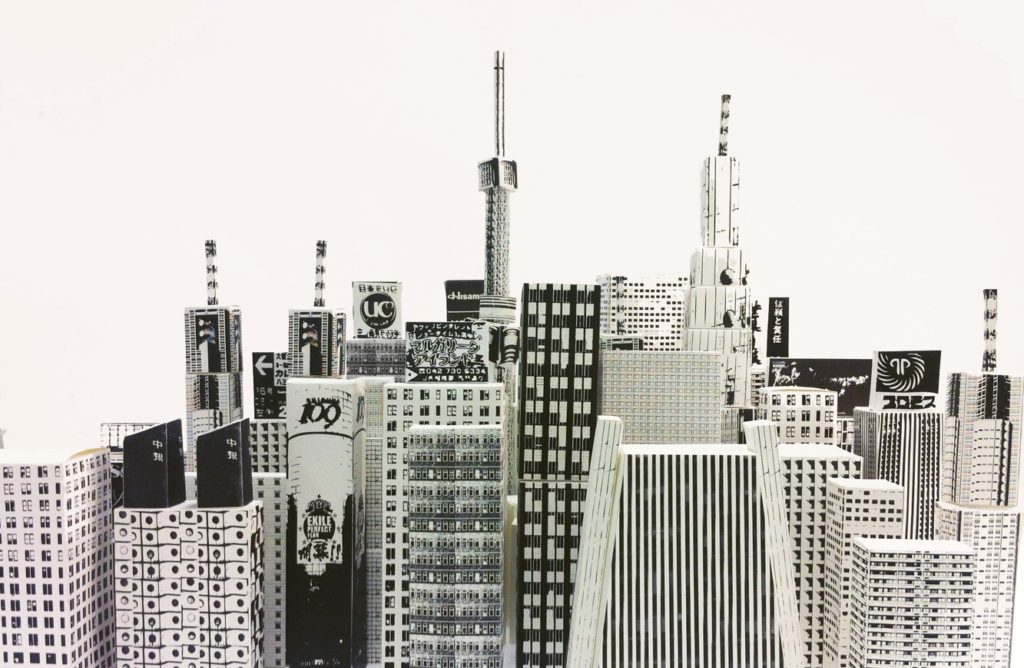

It also served as an inspiration to explore the concept of spatial wrapping in an experiment using paper which is the most common form of wrapping, to create a paper city as an analogy for buildings as a package of people and things.

The question is perhaps best answered by the Japanese view on the function of a package as a wrapping to add layers of meaning which is not communicated in its unwrapped form. On this view, Japanese architecture can be described as a package as its use of seemingly unimportant layers to outsiders, functions to mould, regulate and maintain a harmonic relationship between society, nature and environment.

Spatial Zen

Firstly, like all designs, Japanese architecture has evolved from the need to create a practical solution to adapt to its environment. Japan is a densely populated island where space is a premium. Accordingly, Japanese houses need to be flexible to take full advantage of limited space which it achieves through layering to capture and arrange space. They are designed from inside outwards by reference to spatial units defined by the measurements of moveable tatami mats which cover the entire floor. Sliding translucent paper walls that resonates a level of politeness that does not emanate from a solid brick wall, functions as a wrapping that divides and organises space to accommodate its multi-functional use as a living room, dining room or bedroom depending on the time of the day. Since the walls and mats can be moved, the arrangements are never rigidly fixed and are also able to adapt to contrasting climatic changes characterised by hot humid summers and snowy freezing winters. During summer, sliding walls are opened to allow for greater ventilation and the free flow of air throughout the entire space. It also permits the house to be entirely closed off from the outside during the harsh winters while still allowing diffused natural light to penetrate into the inner areas through the translucent paper panelled walls.

Polite Air-Conditioning

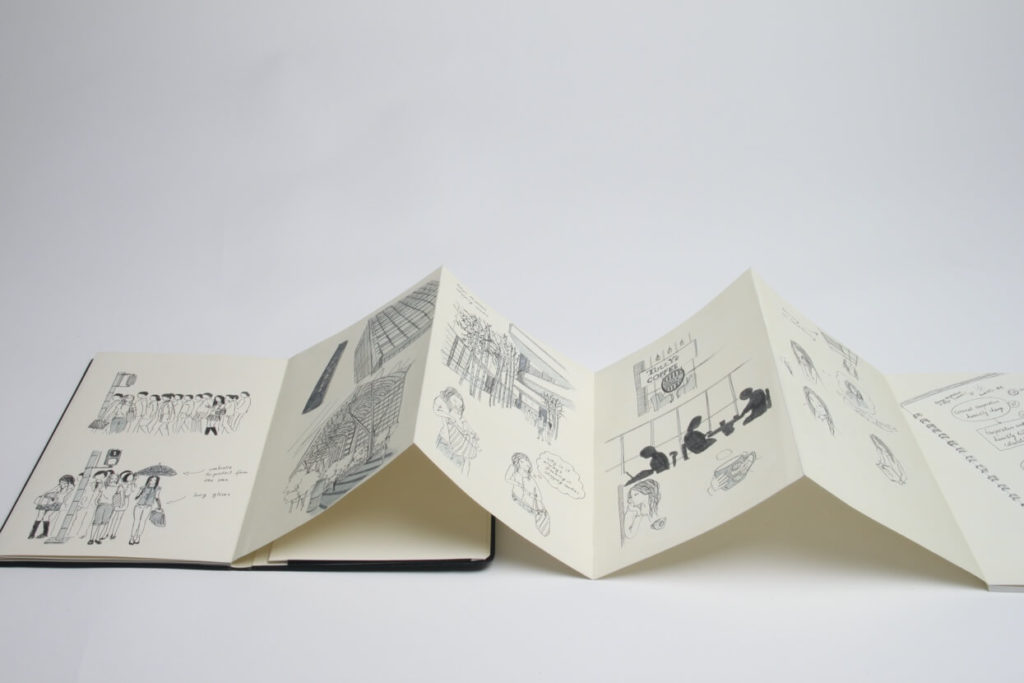

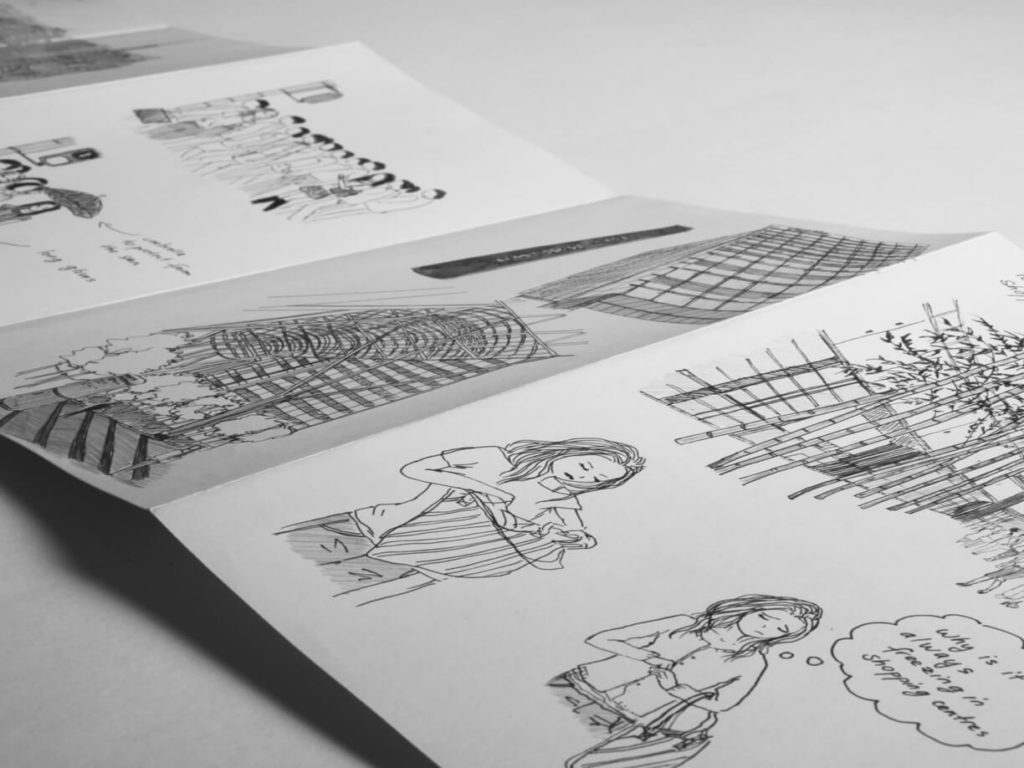

Without experiencing the density of living conditions and the contrasting climates in Japan, it would be difficult for anyone, Western or otherwise to comprehend this design. I only appreciated its practical utility after several stifling humid summers in Tokyo where I loathed the marked drop in temperature in modern buildings from the air-conditioning. I always had to carry a jumper or a coat even when it was 30 degrees Celsius outdoors. There was always a distinct ‘harsh’ boundary between inside and outside due to the variance in temperature. During a hot summer’s day in Tokyo, while having a hot caffeine fix in a shopping centre just to warm my shivering body and blue fingers, I conceived the idea of an air-conditioning system that maintains a constant 8 degrees Celsius between inside and outside. While a difference in temperature remains, it would serve as another layer between inside and outside providing for a more seamless transition between the two. Like a sliding shoji, it would also present a more ‘polite’ means of entry.

Following Nature’s Footsteps

Secondly, layering in Japanese architecture functions to integrate or package man and nature. It incorporates the precepts of Shintoism, the principal religion in Japan, which recognises the sacredness and of every natural object and the spirit that it embodies. This spiritual appreciation of naturalism submits the design process to be guided by it and is responsible for architectural forms that appear an inversion of inside and outside.

Wooden frame construction provides flexibility in an earthquake prone zone. Interiors are characterised by judicious use of environmentally friendly and recyclable natural materials such wood, pebbles, paper and straw; materials that are also used in packaging. Layers of sliding walls are merely temporal screening devices seamlessly extending rooms to verandas and verandas to gardens allowing the uninterrupted flow of the sounds of nature, the aromas of the seasons and the views of the sky and moon.

This fluid exchange between interior and exterior gives effect to mono no aware or ‘man in tune with nature’, a central philosophy for the Japanese. Man and nature are harmoniously wrapped by the flexibility permitted by layering which allows the inside to be open to the outside or, depending on the point of view, the outside to be open to the inside, and yet the inside to be separated from the outside.

While this defies conventional view of a house, when Japanese speak of a house, they do not define inside and outside by reference to whether a space is enclosed but by behaviour and interaction when moving between the layers of space; a point discussed in the next section.

Social Wrapping

Finally, layering in Japanese architecture also functions to provide a tangible structure to the relationships within the enveloped space. Hendry observes:

Paper room partitions still commonly found in Japanese houses may be described as wrapping architectural space and even a smallish house will have inner and outer layers to which visitors are permitted entry according to their social proximity and status.

Hendry, J. Wrapping culture: politeness, presentation and power in Japan and other societies. 1995

It is can almost be described as a tool for social engineering, affecting and regulating thoughts and interactions in society. The best way to illustrate this is by considering the stages of entering a Japanese house, which in many respects corresponds to unwrapping a package; each seemingly unimportant layer yielding unspoken meaning.

The ritual of entering

When entering from a wooden gate, visitors go through the first layer of wrapping in the form of intricately miniaturised landscapes which, like packaging, is an art form in itself. These are usually concealed or wrapped behind a solid stone or wooden wall to provide an element of ‘surprise’. From the garden, visitors then past the next layer of the veranda before being confronted by a noren (split hanging cloth curtain) which allows a glimpse of the inner space just enough to pique further interest and heighten the pleasure of changing prospects. Shoes are then removed and slippers offered; this simple ritual makes a visitor aware that they are going through another layer, providing a gradual transition and polite entry to an outer room of the house. Although inside of a house, Japanese still consider these areas the ‘outside’ as casual or distant acquaintances are generally not allowed further. More symbolically, Hendry points out: ‘the nearer the outside one finds oneself, the more formal the expected behaviour’. Free expression of true feelings are rarely displayed in these areas.

From the ‘outside’ of the house, visitors rarely get a glimpse of the interior as these areas are separated by layers of sliding walls which like packaging, wrap the oku (heart), obscuring it from outsiders and prolonging their anticipation. Oku which refers to the heart, centre or interior of the house also serves as a deeper meaning of the space one is able to express one’s true feelings (honne). In this space, true inner feelings are wrapped and boxed by the paper panels and wooden frames which define the inner sanctum. Within this ‘paper box’ honne can in turn be said to be wrapped or folded by tatami, which is derived from the verb ‘tatomu’ meaning ‘to fold’ and describes the state of the straw mats when not in use. It is this space that is the defining element between what Japanese consider as inside and outside of a house.

This is in contrast to the Westerner’s view of inside and outside of a house which is defined in the physical sense. Consider a façade of windows where the activity inside through the window is just as visible from the outside. Does a boundary between inside and outside actually exist if the separation between private and public areas is transparent? Which is a better definition of the inside and outside of a house? How would people behave at home if they were still in the public eye? Architectural forms have the power to influence behaviour and interactions.

Unlike a conventional house where there is an expectation of an ornate or vibrant interior, those who enjoy close relations with a host and are invited to unwrap the outer layers of domestic space to arrive at the oku are generally met with an unremarkable empty space. Japanese houses exists as temporal layers of captured space and its centre is defined by behaviour when moving between layers rather than a permanent enclosure. It is in this respect that the design of a Japanese house shares the closest characteristics with Japanese packaging; it is the layers that wrap the space or the object that gives it meaning and not the object or enclosed space itself.

An empty centre?

A similar comparison can be made with Tokyo, one of the most spatial and populated cities which defies the conventional design of a city. Unlike Western city centres which are generally characterised by a centre inhabited by a town hall, church or square, Tokyo has been repeatedly damaged by war and destroyed by earthquakes but has always been rebuilt preserving its traditional Edo design of a centre characterised by vast empty space. Roland Barthes describes it as:

The entire city revolves around a place that is both forbidden and indifferent, an abode masked by vegetation, protected by moats, inhabited by an emperor whom no one ever sees: literally, no one knows who does ever see him…Its centre is no more than an evaporated ideal whose existence is not meant to radiate any kind of power, but to offer its own empty centre as a form of support.

Roland Barthes, Empire of the Signs (1970)

The design of Tokyo, like a Japanese house and packaging clearly functions to maintain separation of status relationships, in this case between the ruling class and the masses. But more symbolically and like the character kuni 国, its very existence is owed to and defined by the layers of its populace that wrap it and give it meaning.

In this sense, Japanese architecture functions as a package of people and a mould which fluid relationships are poured and take shape. A house, a city and its inhabitants can be said to be intrinsically part of the same organic whole; neither can be conceived or separated from the other and together can be described as a perfectly designed package. An awareness and understanding to the cultural functions which these forms are based leads to the logical conclusion it does follow design principles. This is true even if the resulting form embeds cultural concepts which we are not familiar with and does not fit within the conventional purpose and geometry of a structure as we know it. But beauty is in the eye of the beholder and our assumptions about beauty can easily undermine any objective analysis of the design process.

Conclusion

It is evident that packaging, architecture and other everyday forms may have different underlying functions from one culture to another. These are rarely explicit to outsiders especially given the veil of inscrutability which some cultures such as the Japanese cloak their own system of beliefs. They have significance for people who use them but as they are familiar objects, may be easily misunderstood by outsiders who make a judgement about the forms they should take based on their own experience. By putting aside the myopia inherent in our predispositions and seeing familiar objects in their own cultural surrounding, we can better decipher the vocabulary that their form communicates.

In this sense, Japanese architecture and packaging serves as a useful case study as it design confounds our Western-centric reading of them. But by putting aside our own bias and taking time to understand and recognise the cultural constructs of uchi and soto that govern Japanese society, the designs unwrap itself and begin to reveal its underlying meaning. Then only do we appreciate that the calculated use of layering in its design functions to add meaning which is not communicated in its naked form. If this is true, then Japanese packaging and architecture can be described as perfect designs in forming an inseparable relation between the outer and inner objects and space that it envelops.

Japan is only the model for the theory developed in this paper but it should be a template that is applied in the design process in any culture, each of which will have its own unique attributes. Like a book, we must read each design in its own native language to savour the full meaning and not judge by its translated text. Then only can we create better designs than we may have otherwise done?